Quilts Remember Our Stories – Historical African American Quilts

How can a quilt become a work of art? How does that work of art tell an important story about those who made it with loving care? How does that loving care shape a story about what the quilt means to a community?

Quilts Remember Our Stories

by jill moniz

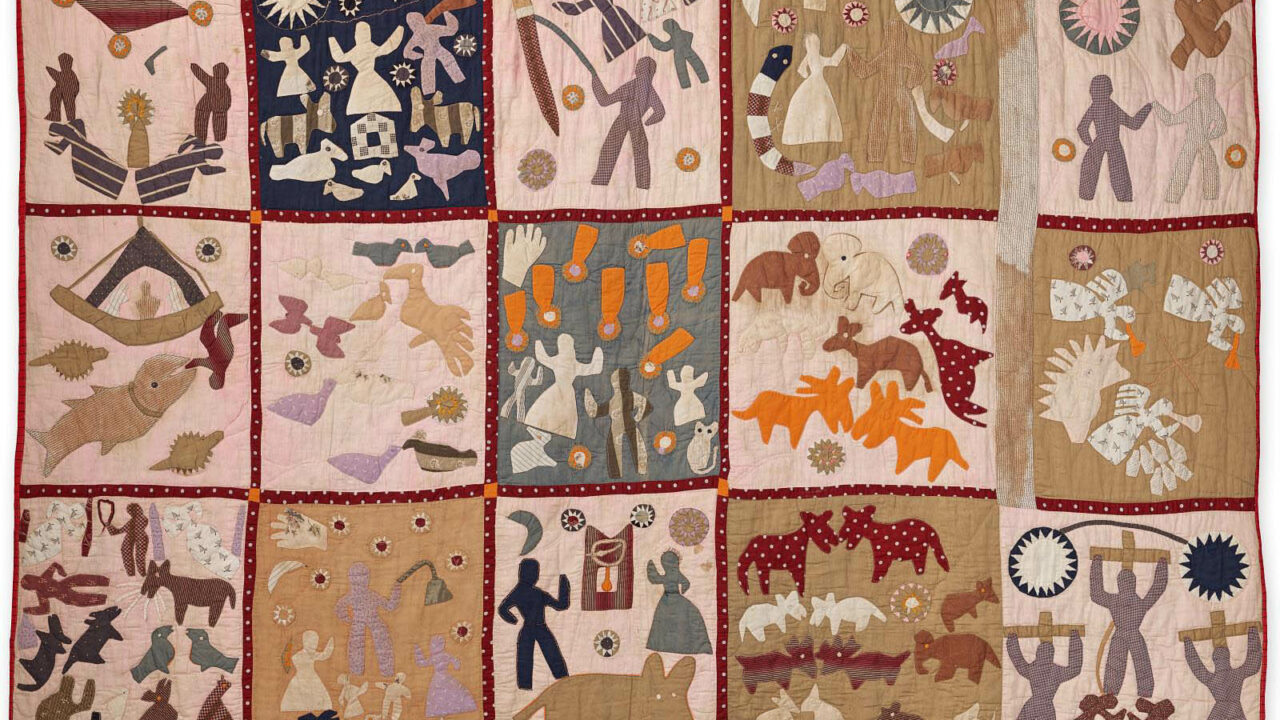

Lavialle Campbell’s quilts reach back in time to Black Southern life and farther back to our African roots where gathering different materials and joining them together to make sacred objects became a way to tell powerful stories. Black women whose labor was exploited in the fields and big houses and later factories used remnants of that work—pieces of uniforms, discarded clothes and blankets from inhumane oppressors—to stitch together love, remembrance, and protection.

The stories created in their quilts are also special for their collective action. They were pieced together as a community, reinforcing oral and making traditions as well as providing respite from violence, brutal and uncaring work, and insecure domestic life. The quilts express moments of triumph and hardship, mothers and children lost to one another, ancestors and future generations who would access these important rituals, traditions and cultural ideas through the imagery and symbols of quilts.

Quilts—or the assemblage of specific and sacred geometry—are what many Black people who came to America against their will remembered to remember. A collage of memories as whispers and songs and celebrations shaped in the patchwork, in which each piece of cloth has meaning. Quilts hold glimpses of time and space and people who held onto who they were by sewing a piece of denim workpants to a bit of an old handkerchief, or a corner of a baby’s blanket. These objects are acts of love and resistance and now hang on walls in museums around the world, recognized as the art of a tenacious people.

Lavialle Campbell and other makers working today use the same language to shape and share contemporary assemblages in fabric. From her monochrome fields to her highly personal stories of survival, Campbell merges and layers history with what Black women’s work and joy is in the 21st century. As the master quilter in residence at Kidspace this month, she is stitching together another experience to add to her repertoire of ideas and symbols.

—jill moniz, phd, founder of Transformative Arts

First image: Pictorial quilt by Harriet Powers, 1895-98.

Second image: Kitchen Sink Quilt by Lavialle Campbell, courtesy of the artist.

Third image: Quilt for Peter I by Lavialle Campbell, courtesy of the artist.